Sof-N-Free, X-Pressions: Black Beauty Still Lifes, 2020

Nakeya Brown

Nakeya Brown was born in Santa Maria, California in 1988. She received her Bachelor of Art from Rutgers University and her Master of Fine Arts from The George Washington University. Her work has been featured nationally in recent solo exhibitions at the Catherine Eldman Gallery (Chicago, IL, 2017), the Urban Institute for Contemporary Art (Grand Rapids, MI, 2017), the Hamiltonian Gallery (Washington, DC, 2017) and The McKenna Museum of African American Art (New Orleans, LA, 2012); and in group exhibitions at the Eubie Blake Culture Center (Baltimore, MD, 2018) the Prince George’s African American Museum & Cultural Center (North Brentwood, MD, 2017), and the Woman Made Gallery (Chicago, IL 2016 & 2013), among several others . She has presented her work internationally at the Museum der bildenden Künste (Leipzig, Germany, 2018) and NOW Gallery (London, U.K., 2017). Brown’s work has been featured in TIME, New York magazine, Dazed & Confused, The Fader, The New Yorker, and Vice. Her work has been included in photography books Babe and Girl on Girl: Art and Photography in the Age of the Female Gaze. She lives and works in Maryland.

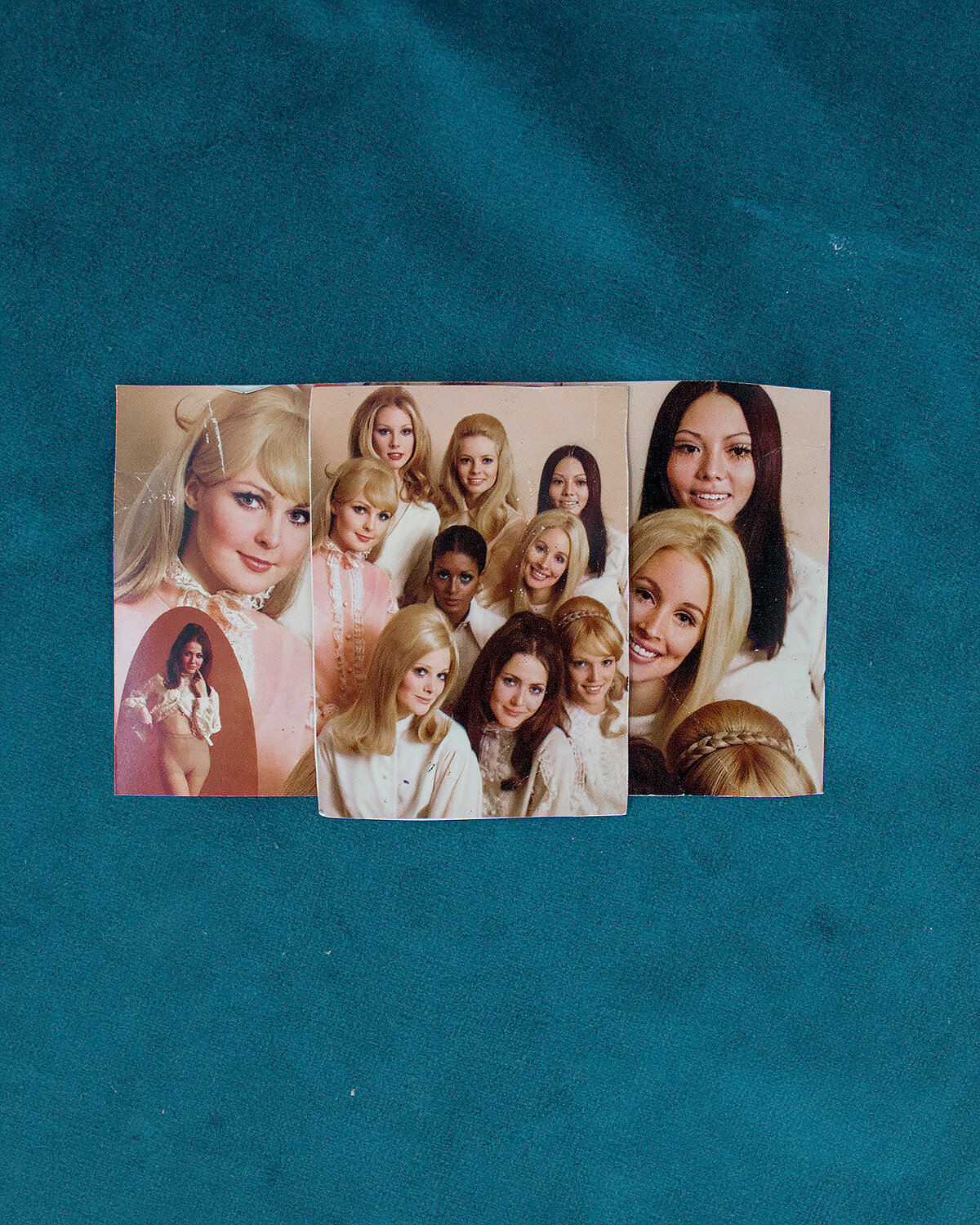

Cameo Appearances (fronts), Cameo Appearances, 2016

Interview with Nakeya Brown

Questions by Sonja Teszler

Lovely to meet you Nakeya, even if indirectly! I wanted to lead into my first question with a bit of a personal segue. I’ve recently been reading and thinking a lot about rituals in the times of COVID and becoming aware of their therapeutic dimension. During quarantine, the most mundane and bodily rituals- like making a meal or acts of self-care - provided a kind of life vest against insanity. They also helped immensely to process certain anxieties or the state of my being. I feel like your photography deals with a lot of such small, personal rituals and so I was wondering if you could talk about this in the context of “therapy” if that sounds relevant? And on that note – how have you been experiencing lockdown?

The lockdown has had its ups and downs. Much of my time has been spent with family, creating a space for us all to get adjusted to the major change our daily life underwent. I’ve been able to finish two books and make work as my schedule allows.

There is a captivating dichotomy in your photographs. They are dreamy, nostalgic and intimate compositions and yet they’re also incredibly powerful and unsettling, presenting the domestic and the body as a site of protest. Could you describe the visual references that have shaped your aesthetic, and its relationship to some of the critical themes in your work?

Beauty supply stores, design and packaging marketed for women and girls of color, Jet and Ebony magazines, braid posters, the still life work of Lorna Simpson, Leslie Hewitt, Jan Groover, Carrie Mae Weems, and Barbara Kasten. My own childhood photos and the images of women that circulate within my family’s archive. The colorful paintings of Clementine Hunter and Louis Mailou Jones along with the abstract works of Howardena Pindell and Gee’s Bend Quiltmakers. Much of my work is about construction in the material sense, but also incorporating Black female subjectivity as a resource for expressing facets of womanhood.

Vidal-Sheen, Gestures of my Bio-Myth, 2015

Photography (and of course moving image) is perhaps the most accessible medium in that it can create visceral worlds that instantly evoke empathy in the viewer. What drew you to photography and have you worked in any other media – if so, how did you approach your subjects differently?

A high school art elective in photography really drew me to the medium as an art form. I’ve used digital, film, and cameraless-based strategies to make my work. In “Cameo Appearances” I extracted cameos from beauty packaging and scanned each side on gray cards. In that series I wanted to explore the shortfalls of representation inherent in using a camera by not using the tool that reinforces it. But as a photographer I’m also interested in exploring the various qualities of images that result from different cameras and do value experimentation.

I find it beautiful how symbolic language, or symbolic objects (books, photographs, hair care products etc. ) and motifs like the ones in your photographs, can be both profoundly personal and yet relatable within a collective mythology. Are you thinking about myths as such in your practice, and how does your personal memory and history inform your work?

I appreciate how symbolic objects assist in the image’s legibility—the ability for a stranger to see the work and find its visual and contextual significance. In my work it’s the “bio-myth” that contextualizes the images as narrators of Black womanhood from my own personal standpoint. Without the collective efforts of Black female writers, I would not know language such as “bio-myth” which was coined by the late poet Audre Lorde. I use personal memory as a starting point and history as a frame—conjoining the two creates a body of information which is the “bio-myth”. All this this is enclosed in the photograph, and so my photographs are encoded with all of these layers of meaning.

Your photography has a very evocative, unique language – the images are precisely composed and the objects, patterns, textures and colours all seem to carry their individual symbolic significance. What’s your process of choosing the elements of and curating a picture?

Typically, I always start with a striking object or memory that I want to translate into a photograph. That object might be an old photograph, beautification device, magazine tear, etc. I then isolate that item against a seamless, color-aid, or sheet that accentuates the tone of the image. It involves quite a bit of shifting, placing, and removing objects based on their symbolic importance, color, scale, and shape.

Food for ‘Good’ Souls, The Refutation of ‘Good’ Hair, 2012

Though the theme of hair appears throughout your whole oeuvre, your two series “The Refutation of “Good” Hair” (2012) and “Hair Stories Untold” (2014) in particular address questions around femininity and race directly through the lens of hair politics. I was wondering if you could talk about the progression of these bodies of works in terms of inspiration, differences and similarities in their approach to the subject, visual leitmotifs and the process of working on them?

None of the women in those series are strangers to me, but rather people I knew closely and were willing to collaborate on a project that reflected on how Black women navigated the world. Over the span of the years that it took me to complete the two series I was coming into a feminist consciousness to help articulate the importance of what I was doing with my photographs. Both center the Black female experience through the construct of femininity based on hair texture. In both series it was important to express how these ideals have been rooted in whiteness, but Black women have developed different modes to resist that subjugation through the cultural expressions of our own bodies. In terms of hair texture, those forms of resistance include braids, the natural/afro, twists, weaves, and other forms of protective styles—including, scarves, caps, and head wraps.

Your work is critical of the racial and gendered biases around the construct of beauty itself. You subvert a lot of the imagery and commodities known from visual culture of mass production and advertising that systematize fraught beauty standards, specifically related to hair. Could you elaborate on the visually subversive aspect in your photographs?

I use arrangement and placement as methods for disrupting the legibility of the photograph. I’ve used these methods to prevent the photograph from displaying the narrow representations of Black women as only to be seen as “acceptable” through the act of hair straightening, for example. This can be seen in “Facade Objects” where I obscure the female faces imprinted on perm boxes using the kit’s content. Where and how objects are placed before the camera can determine how we read and understanding the image’s messaging.

Don’t You Know Love When You See It?, if nostalgia were colored brown, 2018

Your practice engages strongly with nostalgia in its general aesthetic and explicitly in series such as “If Nostalgia Were Colored Brown - (2014-2019)”—is this relationship towards nostalgia critical, celebratory or both?

It works in both ways but requires a particular type of engagement with the work that goes beyond just seeing. If Nostalgia Were Colored Brown is about joy, laughter, the enchanted moments unseen within Black womanhood materialized through the ordinary and every day. It culls objects of the past for the early inklings of our modern day ‘black girl magic’. The legacies our grandmothers, great-grandmothers, aunts, cousins, and sister friends paved out of these public and private avenues of their daily life. It is a thinking of the past through the sentiment of small pleasures. For Black women—historically and now—self-care and joy is wrapped up in small everyday pleasures underneath the interlocking systems of oppressions of race, gender, and class. To fully understand my practice is to understand the explicit choices but also the implicit realities that have shaped them.

I feel like physical photographs themselves in the old school-sense are very powerful, rich tools of archiving one’s own history (but maybe I’m just being nostalgic.) Is the materiality of a photograph something you consider important, or how do you think this personal, symbolic function has changed over time with digitalization?

In this age of digitization, we are so lucky that the archive doesn’t have to exist in the shadows of obscurity. It can in fact be mobilized and contextualized in ways that allow for more perspectives to be accessed. So, digitization has the potential to undo some of the very problematic issues that are still prevalent within photography’s history & culture. Some of my favorite archives right now are Black Archives and Vintage Black Glamour.

In relation to your work’s engagement with rituals of self-care, I was wondering what you thought were ways to nurture community on a bigger scale?

Nurturing the community needs starts with caring for children and families. How can we create experiences, services, and opportunities that benefit the complexities of children—our future—and the American family their safety net? As a mother it’s difficult to imagine the act of nurturing in isolation. Ultimately a nurtured community is one where its members feel and are safe from violence in their daily life irrespective of class, gender or race.

Accent African, X-Pressions: Black Beauty Still Lifes, 2020

Is there an artwork, film or piece of writing that particularly inspired you recently?

Recently I watched ‘Drylongslo’ by Cauleen Smith on Youtube. It chronicles the semester of a young woman enrolled in a photography class. She focuses on taking snapshots of men out of fear that one day they will all be gone. I don’t think I’ve seen a movie that has dramatized that amount of shared experiences! It was all the way inspiring from a narrative point. I also enjoyed the small still life vignettes that appeared in Pica’s house. I kind of got lost in the visual world of her every day and that was especially inspiring in this moment.

I was wondering about the relationship between your writing, your poetry and your artistic practice - as someone who also writes and enjoys poetry, I often think of pictures almost as visual poems. Do you see a lyricism in your photographs? Do you have a piece you wrote that’s particularly close to your heart?

When a photograph illustrates the unexpected it becomes lyrical in its own way. Once I decided that I wanted to explore lived experiences through object-driven representations of that, I had to embrace the poetic nature of my work. I turned a lot to Black feminist texts to find the language to describe my interests. Occasionally I’m moved to illustrate the themes within my photographic practice in the form of poetry, though as of late a lot of lyricism can be found in my series and image titles. A favorite piece of writing of mine can be found in the Journal of Feminist Scholarship and is entitled “A Delicate Knot: Photographing Black Girlhood and Womanhood”. A newly published writing entitled “Pressing Close: Black Women Making The Still Life” is currently living on my blog for anyone to read.

What are you working on at the moment and is there anything exciting you have coming up?

I am completing a Sibyl’s Shrine Residency for Black women, womxn, trans women, and femmes who are mothers and identify as artists. Shortly after I will be presenting a solo show entitled X-pressions: Black Beauty Still Lifes at the Delaplaine Arts Center.

To find out more about Nakeya and her work, check out her website.