Tom Lauerman

Tom Lauerman is an artist & teacher creating artwork with clay, code, and craft techniques. His work is populated with references to archetypal forms from the built environment, including arches, pilotis, stairs, domes, and colonnades. Often, his works are small in size while suggesting a monumental scale. Textures in the work are often elaborate and highly articulated abstractions of tiles, shingles, bricks, and stones. His work typically begins in a digital space and is later materialized in physical materials, primarily clay. He has designed and built a number of custom 3D clay printers he uses extensively in his studio. He combines contemporary digital fabrication processes with ancient craft techniques. Recently, he created hybrid digital/physical works via claymation, illustration, and interactive 3D models. He has taught classes and workshops for a number of years in 3D modeling, 3D printing, Ceramics, and Sculpture.

Tom Lauerman working in the studio.

Interview with Tom Lauerman

Questions by Emily Burns

Can you tell us a bit about your background and how you became interested in becoming an artist? What were some early influences? Any stories that stand out in your mind?

If we met in elementary school I would have told you I wanted to be an artist. I was always drawing as a kid, and I guess I am always drawing now.

I remember my introduction to working with clay. When I was 5 or 6 years old my Mom signed me up for a Summer clay workshop at the local middle school. I remember cleaning up at the end of each session. I loved rinsing the red clay out of the sponges we had been using. I found this cleaning/filtration/dilution process hypnotic. I wouldn’t have known at the time that the natural sponge was once a living sea creature and that the clay was once part of a mountain that had since been eroded and transported through wind, rivers, and streams, until it settled down someplace as a damp mass of moldable earth. I don’t have a clear memory of what I might have made in that class but I can remember something compelling happening between animal, mineral, and water in the sink.

What gets you in a creative groove? What puts a damper on your energy?

I work best when the studio activity is a consistent daily habit. If I work in the studio every day, even for a short time, I feel calmer, more connected to things, better able to prioritize things, more insightful, and I am much easier to be around. It has taken a long time for me to separate the joy of just working from external things like exhibitions, sales, and broader recognition, etc.

I don’t work well under pressure. Trying to work every day is also a hedge against having to rush a project to completion or make decisions under too much stress. A lot of my works, despite being small in size (but not scale), take years to gestate.

Fluid Form, glazed ceramic, 3.5” x 3.5” x 5” (9cm x 9cm x 13cm)

Can you tell us about your studio? Any unique aspects that make it particularly suited to your practice?

My studio is in our family home. My wife, Shannon Goff is an artist, and we have two kids who like to draw and work with clay, computers, and 3D printing. We share the studio with a pet rabbit as well. Sometimes the whole family is in the studio, other times it is just me and the rabbit.

I’m very particular about how things are set up, so what is unique about the area of our studio where I work is that it is organized as closely as possible to my notion of an ideal working space. There are eight 3D printers in the studio at the moment, two for clay and six for plastics. I designed and built the clay printers over a period of years, so everything about them is really connected to ideas I have about material, texture, and form. There are a pair of small kilns, and one larger kiln. I have a very good desktop computer, where all the projects are drawn/modeled/coded. I have a lot of ceramic materials for making clay bodies, slips, and glazes. I love testing materials, so I have a lot of scales and little jars containing metal oxides and earthy minerals.The place has a bit of a laboratory feel to it.

When I don’t have a good idea to work on or an object I’m presently excited about I can always turn my attention to making a test or sample. In ceramics there is a tradition of making “test tiles” as a means of learning about a particular clay material, glaze chemistry, texture, tool, or technique. In truth I approach everything I do as if I were making a test tile. I could talk for hours about what I’d call a “test tile mentality”.

You often use a small test kiln to fire your work--can you tell us about that choice of methods? I bought a small test kiln immediately when I left grad school for about $400. It was a great investment as I still use this kiln more than any other even now. The kiln has an interior dimension of 8”x8”x9” (20x20x23cm). Much of what I make fits in this volume. Kilns that small can be plugged into any household outlet. I have been able to use this kiln in studios I’ve had in Chicago, Texas, and a couple locations here in Pennsylvania.

What type of kiln are you using?

I made a decision a few years ago to stop using fossil fuel powered kilns for environmental/sustainability reasons. Electric kilns, when powered by a utility that focuses on renewables such as wind and solar are the best option from an environmental perspective and offer excellent programmable control and repeatability.

However, sometimes the precision and tidiness of electric kilns can feel somewhat bland. So, something I am very interested in at the moment is “pit firing”, basically making a small smoldering bonfire in which the work is fired, exactly as the earliest ceramic artifacts were processed, millenia ago, before the advent of a proper kiln.

I live in a densely wooded area, and I make small sized work. Therefore I can walk around in my backyard and gather enough fallen branches to periodically complete a small firing without ever cutting down a tree. If the clay being fired also came from the same backyard that is even better. There is a lot one can do with the materials that are just underfoot. Recently people have started using the term “wild clay” to describe clay one finds locally, as opposed to something that is commercially mined on a larger scale. Working with wild clay and experimenting with primitive pit firings presents a contrast to designing forms in software and forming them with robotic assistance via printing.

What are the benefits of firing one piece at a time in this way?

If you conceive of everything you are doing as a series of tests and iterations it is very helpful to be able to get results quickly, in order to keep an experimental thread of work going.

A small volume can heat up and cool down more quickly than a larger volume. But also, you don’t have to wait a long time just to have enough work to fill the kiln. From an energy standpoint it is very efficient to heat a volume that is about the size of a melon.

You often employ digital fabrication techniques, has that vein of interest always been present in your practice?

When I was growing up the tools I use now either didn’t exist or weren’t accessible outside of a few very niche industries. I have an undergraduate degree in Painting. I stopped painting a year or two after I graduated and began working with sculpture and ceramics instead. In graduate school I focused on Ceramics and sculpture in very analog ways. Toward the end of grad school I was able to use fairly basic 3D modeling software the architects and designers were engaged with. At that time, for me, it was only useful to create a sort of blueprint - I had no means of shaping material via automated tooling. After grad school I started teaching myself Blender, and over the years I have watched with delight as this software has evolved and improved as a global open source effort. At various places I have taught I was able to learn and use a variety of tools from laser cutters to CNC milling tools, and eventually 3D printers. Once I started experimenting with 3d printing clay directly I knew this was going to be the most impactful tool for me going forward.

What draws you to these methods?

My Mom was involved in the early computer industry, in the 1960's. She grew up on a farm that lacked electricity and running water when she was born, but ended up studying math at Southern Illinois University and later worked at Bell Labs, working in the FORTRAN computer language on projects that included processing rocket trajectories for the space program. She left the workforce when my brother and I were little, but never lost her enthusiasm for computation as a powerful and creative force.

As a result of her experience she encouraged us to engage with computers, and convinced my Dad to buy a personal computer super early on, before they were very mainstream. My brother and I did lots of coding stuff and experimentation as kids, even though we were very arts oriented already.

So, I had a love of computers, and creative computing from the start. For many years this interest had no outlet in my artwork, but over time I found more and more ways to get back to the joy of my earliest experiences with computers. During the years when I had no reason to use computers in an artistic way I was fortunate to be able to study things like figure drawing and oil painting and get a very traditional education in studio art that became the other half of my hybrid approach.

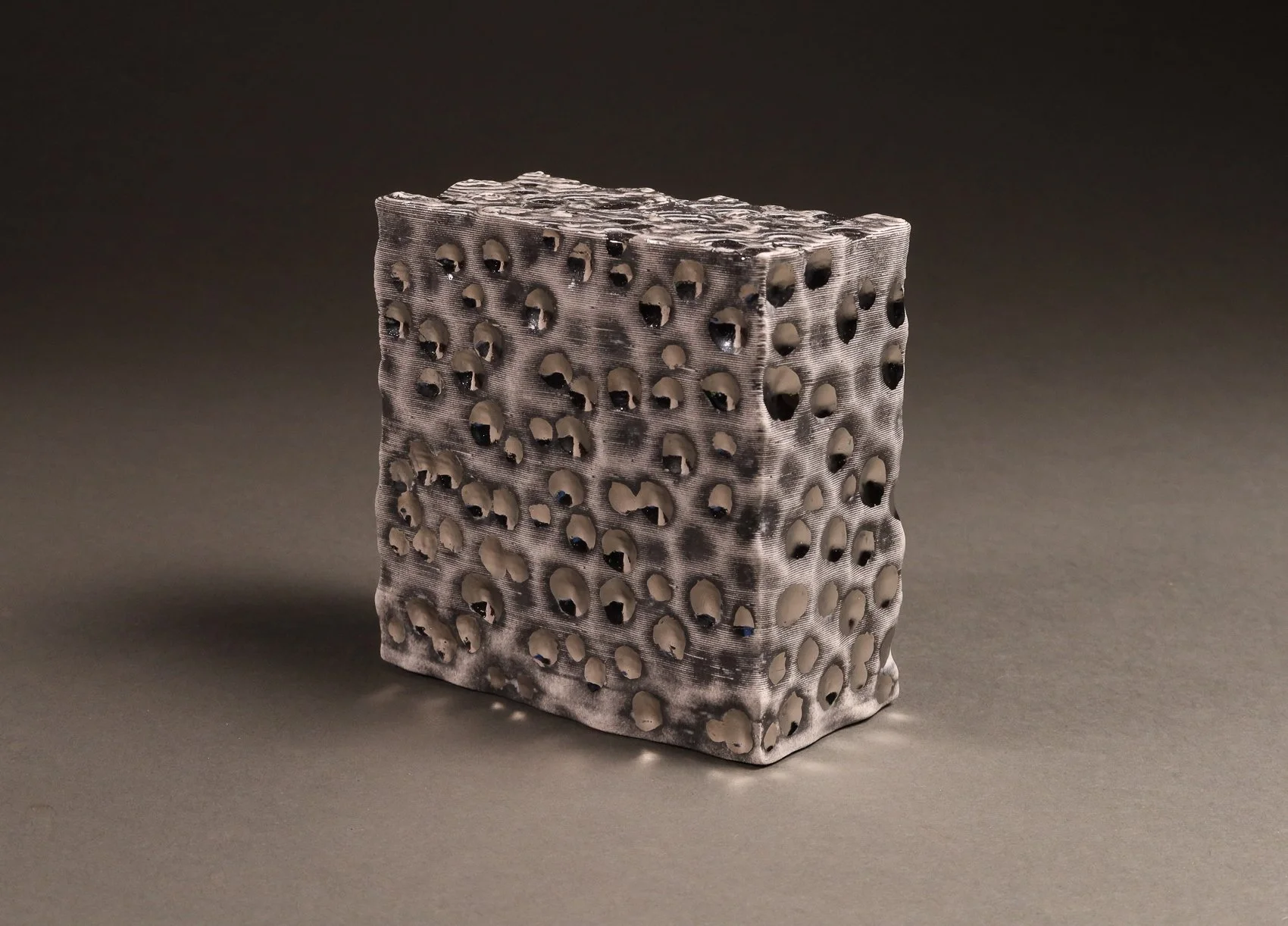

Voronoi Block, 2022, glazed ceramic, 3.75”x 2” x 3.75” (9.5cm x 5cm x 9.5cm)

I imagine that fabrication techniques require preliminary design and planning--does this mean that drawing plays a central role in your work?

All of my work begins in a drawing process, which can be analog or digital. Quickly that becomes a 3D model, usually created in Blender. Blender is the tool I use more than anything else in the studio. It is incredibly versatile and objects can be made via sculpting, modeling, coding, node-wrangling, or through various modifiers. I feel very connected to Blender and the open source community around it.

So the big challenge in my work for many years has been working through how a digital model becomes a physical object, preferably in fired ceramic. There are a few pathways one can follow, usually by adding, subtracting, or cutting, folding, or stacking material according to the model’s parameters.

My teaching revolves around exploring all of these pathways and the tools that facilitate them. These include (in order of complexity and cost) scissors, pen plotter, vinyl cutter, laser cutter, 3D printer (consumer grade), CNC milling (DIY style), 3D printing clay (bespoke style), CNC milling (industrial scale), 3D printing exotic materials. Drawing facilitates all of these processes, in the sense that what is needed is a toolpath, and in my mind a toolpath is just a drawn line in both digital and physical space.

Much of your work is 3D printed--is that the primary method by which you make your ceramic work?

For me, printing in clay, using a printer I designed and built specifically for my work has been profoundly empowering and exciting. I began working toward this goal around 2015, and sometime around 2020 got to the point where I just feel totally fluid with the process. This is my primary method of shaping clay and likely will continue to be.

Shingle Sided, 2022, ceramic, 6” x 3.5” x 6.25” (15cm x 9cm x 16cm)

Are there any exciting new fabrication techniques on the horizon that you are excited about?

Not so much, at the moment, at least as far as hardware or tools are concerned. 3D printers have matured to a point where recent improvements feel evolutionary rather than revolutionary. Physics and gravity have their limits, so increases in speed and resolution and overall quality will be relatively slow via hardware improvements.

I am excited, and sometimes frightened, about advances in AI and all the ways those advances will impact creative endeavors. I follow a lot of artists using generative coding systems and AI tools and techniques. One of the things that I am having trouble wrapping my head around at the moment is just how explosive productivity can be within those systems. A number of generative and AI artists I follow, and whose work I admire, create thousands of individual artworks each year. This has to be outpacing nearly any artist or art movement in history. If I were to create 1 artwork per month for a year I would consider that an incredibly productive stretch and I am certain I would have had to make all kinds of personal sacrifices in terms of time/sleep/health to make it happen.

The way I pursue 3D modeling is in some ways very old fashioned in that I do like to move things around one point, one plane, one edge at a time. I compose in digital space in much the same way I would if I were constructing with wood, metal, or clay. I spend just as much or more time on it. I should be clear, I don’t think I save any time at all with digital tools versus analog, especially if you factor in the time invested in building machines.

A possible route to greater productivity for me as an artist would be to conceive of my projects as generative systems. I do use tools that are sort of adjacent to and affiliated with these ways of working. For example, a cityscape model in which many modules can be randomly shuffled and reconfigured in software leading to some number of novel constructions. In some ways I think I’m being foolish and stubborn by not pursuing more generative modes of working.

In the studio however, I like to be able to focus on tiny details. I don’t know if I could manage a large set of outputs, conceptually or emotionally. I am easily overwhelmed by things. This is another reason working in a small size appeals to me.

Stepwell, 2022, glazed ceramic, 3.25” x 3.5” x 3.25” (8.5cm x 8.5cm x 8cm)

You have built kilns and 3D printers from scratch which is an impressive feat. It must be rather freeing to have the skills and knowledge to build the actual tools that you can then use to create your work. How did you become interested in this type of building, and how did you go about learning how to build these tools and machines?

This is at the root of everything I do as an artist and teacher. I try to tap into overlooked resources, local materials, DIY tools, and open source software. I often print with clay I dig in my backyard. The printers I use are made from scratch with aluminum extrusions I cut and shape, and inexpensive control electronics that are open source. I really try to steer clear of expensive processes, proprietary software, and tools that can’t be readily reconfigured and altered. It has always been important to me to embrace the aspect of art that is about making something from almost nothing.

I didn’t have any training in kiln building or mechanical engineering or 3D modeling, but I’ve always been a tinkerer. My brother and I would often take apart our bicycles as kids and try and improve them in various ways. When I started working with clay I read a lot of books about kiln building and glaze formulation. I started conducting little experiments, building little kilns. I talked to classmates and coworkers, always asking technical questions and taking notes.

Early 3D printers were so poorly designed you had no choice but to repair them constantly if you wanted to use them. It was also much cheaper in the early 2010’s to get started in 3D printing if you were willing to build an open source design following someone else’s instructions. This turned out to be a kind of conversation via tool making that I really enjoy. I’m really glad I got into 3D printing when I did, and struggled so much with it. Building experimental open source printers gave me the confidence to make changes to the existing designs of others and ultimately to just build my own version of a clay printer from the ground up, and to constantly iterate on those designs.

I have been so fortunate to meet many amazing artists and designers and engineers who have helped me understand materials, tools, and processes.

Using a small-scale kiln limits the scale of your work, but I imagine there are fabrication techniques that would allow you to work much larger. Have you ever worked at a larger scale or with materials other than clay?

I don’t think of my work as small in scale, even when it is small in size. The works are conceived in a digital or virtual space in which their scale is not fixed and they don’t have to contend with gravity and materiality. Sometimes they are exhibited in ways that scale can be elastic, as when projected or displayed as video.

The proportions in the work most often reflect architectural spaces: arches, staircases, colonnades, domes, and vaults. I hope the work invites the viewer to project themselves into the space of the work. I want the work to function in some of the ways an architectural model works.

Folding Screens, 2022, ceramic, 9” x 2.25” x 5.25” and 6.5” x 2.5” x 5” (22cm x 6cm x 14cm and 17cm x 6cm x 13 cm)

Are there any contemporary artists you’re currently really excited about? Any favorite exhibitions you’ve seen recently?

I'm following lots of digital artists presently.

I love the work of Satoshi Aizawa, who makes abstract looping animations, often of a single line in black and white, that find an incredible balance between simple and complex, precise and chaotic.

I am really interested and nervous about the use of AI tools/processes in art. I follow a number of artists who are pioneers in AI art, but the one I connect with the most is Helena Sarin, who is both insightful and funny, accomplished and approachable. I have a sense of how hard Helen has worked to create truly unique AI datasets, and I appreciate her efforts to connect the work to past and present movements in art , design, poetry, and science.

Auriea Harvey is another artist I’m excited about. Auriea’s eloquence regarding the complexities of moving between digital and analog modes is refreshing and insightful. Auriea takes an approach to working with digital/analog hybrids that relishes a kind of messiness that most artists avoid by either pushing the digital work to the foreground (in new media art) or the background (in painting, sculpture, etc).

I feel that the boundaries between digital and physical works are less obvious than they might appear. I like to think anything mediated by the “digits” that are our fingers is digital, at least in one sense.

I am always looking back at art history and architecture history, particularly as it relates to clay and ceramics. Something I love about my hometown, Chicago, is the range of architectural expression in both the noteworthy structures downtown and the more modest structures found in every neighborhood. I miss riding a bike through the city, taking note of the textures, surfaces, and patterns.

Do you have any tips, tools, resources, or advice that you have found particularly helpful?

I’m a teacher, so I have way too many tips and advice. The most important is to find and develop your own voice and not to work towards some received idea of what art is supposed to do and supposed to look like. The parts of your work that you find most embarrassing in a critique are likely to be the most resonant to an engaged viewer.

Various recent works, 2021, ceramic, dimensions variable.

What's up next for you?

I’ve been in the middle of a kind of pivot for a few years. A huge amount of my effort over the last half decade went into developing a new way for me to work, via the custom clay printers. I feel like my brain rewired itself during that time, and I was focused on a thousand little engineering challenges. This was research in sort of the traditional sense, it wasn’t about self expression, or it was a kind of self expression via mechanical engineering. During this time I exhibited less, and often exhibited older work. Now I am coming out of that mode. I feel like my brain is again being rewired, shifting focus back to narratives, textures, rhythms. I hope to exhibit more often, share more of what I am doing, and basically make a slow pivot from a kind of inward facing learning and building process to a more public facing sharing activity.

Anything else you would like to share?

I really appreciate the opportunity to present work in Maake, thank you for creating this wonderful publication and allowing me to participate.