Sonia Louise Davis

Born and raised in New York City, Sonia Louise Davis is a visual artist, writer and performer. She has presented her work at the Whitney Museum (NY), ACRE (Chicago), Sadie Halie Projects (Minneapolis), Visitor Welcome Center (LA), Ortega y Gasset (Brooklyn) and Rubber Factory (NY), among other venues. Residencies and fellowships include the Laundromat Project’s Create Change Fellowship (NY), Civitella Ranieri (Italy), New York Community Trust Van Lier Fellowship at the International Studio & Curatorial Program (Brooklyn), Culture Push Fellowship for Utopian Practice (NY) and, most recently, Lower Manhattan Cultural Council’s Workspace Artist in Residence Program (NY). Her forthcoming book, “slow and soft and righteous, improvising at the end of the world (and how we make a new one)” will be published in 2021 with Co—Conspirator Press, a publishing platform that operates out of the Women’s Center for Creative Work in Los Angeles. An honors graduate of Wesleyan University (BA, African American Studies) and alumna of the Whitney Independent Study Program, Sonia lives and works in Harlem.

Statement

My sculptural objects and installations, performances and experimental texts are grounded in Black studies and informed by my training as a jazz vocalist. For the last five years, improvisation has been at the center of my work. My sensibilities as an improviser impact my choice of materials, my movement across mediums and the ways I interact with the varying techniques I employ: from weavings and works on paper, fabric and found objects, to durational live events that feature voice, breath, and gesture. I situate my practice within a lineage of Black feminist abstraction, and the thinkers I gravitate towards speak urgently of emergence, deep listening, waywardness, indeterminacy, adaptation, world-making and collaborative survival. Holding on to its vernacular meaning, improvising is a way of making do with what you’ve got, pulling from the resources of your past experiences to generate something fresh and unforeseen in the present moment. It’s about trust in self. It’s my methodology, and guides the way I listen in the studio as well as my active engagement with the outside world.

Interview with Sonia Louise Davis

Questions by Nancy Kim

Music plays such a strong role in how you think and how you exist in the world. How has your background in Jazz and Black Studies shaped how you think about and how you create your pieces?

As a listener and a participant, music has been in my life as long as I can remember. I sang in choral groups throughout elementary and high school, and with instrumental jazz ensembles every semester in undergrad. I was a Black Studies major because those were the classes I gravitated towards, where I found both inspiration and a critical lens to examine the world around me. I felt at the time that music was an activity outside of my academic coursework, but eventually I saw that it was absolutely the creative outlet I needed alongside everything else I was doing. I’d always really valued rehearsal because it’s the place you get to try things out, make mistakes, and learn from them. I wasn’t focused on the gig as much, or driven by the audience you get in a performance setting. Several years later, when I was making visual art, I realized how significant that training was in terms of giving me space to be experimental, to take risks within a supportive community, to practice listening and excellence and collaboration.

Once I graduated I didn’t pursue jazz singing, but I think a turning point came for me about 5 years ago when I found I was craving the feeling of singing, just in a different form. I was seeking out a creative, judgement-free zone like the rehearsal room, and I tried to capture that energy inside the studio, which I should say, for me is conceived of as “expanded” in the sense that I don’t always rent a physical room or identify my art practice as only happening in a particular location. Initially this seemed like a limitation (I couldn’t afford to pay NYC studio rents), but I turned it into an asset (I can make work anywhere, I already am.)

Jazz gave me an introduction to improvisation as a disciplined practice. People tend to associate improvising with a worst-case scenario, like, "something went wrong so I had to improvise," but when we shift focus to the improviser, a totally different understanding is possible. A good improviser brings awareness of what her talent and unique perspective can bring to the challenge at hand, and must assess in real time/in the moment what needs to happen. It’s a responsive practice, not simply a reactive one. Over the last 10 years making art in my hometown, NYC, I’ve tried to carve out space for a critical creative practice that is generative and expansive.

Can you talk more about that feeling of singing in your work? The way you use marks and space often give your pieces a quality of captured movement--a feeling of live compositions or moments caught in motion or anticipated motion. Are there approaches, philosophies/principles, or structures in jazz that inform your process? How do they inform the visual elements or compositions of your pieces?

It's actually hard to articulate, but I can say it's an awareness and a precision and a vibratory frequency, and above all, a flow. When I remember the feeling of singing, I'm in a headspace where I'm truly present, I'm not concerned with the millions of distractions of any given moment. If I'm really feeling it, my eyes are closed. It's just ear and voice. In my visual artwork I think there's definitely a connection to lyrical gesture and movement, as you say, but there's also a tension between the act of spontaneous creation and the measured training and time it took to get there. Maybe this is why I love rehearsal so much, it's impacted how I imagine what the creative space of the studio can be. A few years ago, as a warm-up ritual to start the day’s session, I created a vocabulary of gestural marks. I used liquid watercolor in small journals and tried to move quickly. It was less about each composition or each page individually and more about the accumulation of marks. I noticed certain marks and groupings of marks kept coming up, and that repetition was significant. Eventually this became my graphic notation and the process reminds me of ear training, how musicians drill muscle memory and practice intonation.

My experience singing with instrumental ensembles taught me about collaboration and difference: every player gets a solo, and the rest of the band's job is to back them up accordingly. If it's the upright bass, we all need to be quieter so it can be heard. When we get back to the melody and the singer comes back in, maybe the drummer will switch to brushes so the vocals stand out more. It's a pretty simple concept, but I think it informs a central aspect of my thinking and striving towards a better world: creating an environment for everyone to thrive.

The journals are a ritual I return to often, to practice the gestures and to notice the negative space. The quality of my line can be a kind of indicator, it holds any doubt or trepidation if I’m overthinking it. Instead, I try to get to a headspace that’s similar to singing. When I first started I kept calling it singing without singing.

quartet choreography, 2018, acrylic on four sheets of Fabriano black notebook paper, 8in x 4in, each

Singing without singing...

Yes, what’s fun about it is that you don’t know where you’re going to end up. But those little journals and drilling those marks became akin to the kind of rehearsing and training and singing that one does that isn’t singing a song, but is training your ear to be in tune or training your muscles to reach that high note, to make those interval changes or to hear the kinds of notes and tones that work harmonically in the piece. For me it’s all super intuitive. I’ve always been told I have a good ear. From a young age I could sing along to a melody or harmonize with it, or notice certain other things happening in the music. I didn’t study music theory, I got better by doing. The graphic notation was a starting place, it centered and grounded me in the studio, but it was also something that I realized could become active, used like a score for future performances or installations when it’s transposed to the wall or the floor. quartet choreography is a suite of works on paper that feature the notation. I used one color at a time. The result feels full of movement and makes me wonder how different performers will interpret the material. undersong (for audre) is another graphic notation piece with crayon and liquid watercolor. The wax acts like a resist and affects the way the ink pools on top. In general, though, when I pivoted five years ago towards studying improvisation, I also shifted from working in a project-based way towards trying to create a practice more broadly speaking. There’s an intention around honoring the whole instead of zooming in and narrowing and focusing. I knew I was doing something a little more ongoing.

That makes sense. You were searching for a more whole, holistic view, right?

Absolutely, and that necessarily meant that my attunement was greater. I was noticing that improvisation could be a way to talk about how we are subjected to a great many outside forces (many of which are evil) or how we could talk about the structure that makes people precarious or how we’re often split off from each other, competing instead of collaborating. I found that improvisation could be a way into these conversations I wanted to be having. This also keeps going back to the ritual aspect of practice, this discipline, which is very much self-love and self-care and trust based, asking “how do we care for the improviser?” There are certain activities I wanted to implement that are good for you, that nurture, that are life-affirming.

It seems like there is also a resistance to having to think or act hierarchically while in the making process. Working out of mental hierarchies gives birth to judgement and sometimes too early. How important is to pull back from that self-criticality while making? How important is it to make as if no one’s watching?

I mean to some degree that necessarily happens as artists, especially after the work is finished and you’re making a show, you have to get to a strong edit, but in the actual making, in the process, I’m trying to turn off that judgement because it means that certain things aren’t going to be allowed to happen. I can talk about this in terms of singing a jazz standard: you know the melody, you have to get through it, and then you can do almost anything else. What was really fun for me in rehearsal (which means there’s no audience so your view is internal) is that your solo can take you someplace else. The band is still playing those chord changes (the set of chords that make up the song and where the melody fits in). Those chord progressions keep happening when there’s a solo, but the soloist gets to go as far away as she wants from what’s familiar and then find her way back.

an overtone (for M), 2018, acrylic on found glass frame, with wall painting, 19in x 24in x 1.5in

It sounds like what you’re saying—this kind of chord progression—is like a tether, where you can freely explore and always come back home when you want to. Is this how you build structure?

It is! It’s a structure and a structuring device in music that is tonal. Of course, once composers and musicians decide we don’t have to be linked to anything, we don’t need that tether, then all sorts of interesting, dissonant, atonal, radical outcomes become possible (there is an incredible book by George Lewis on the history and development of the AACM [Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians], which is an ongoing community of Black musicians founded on the South Side of Chicago in the early sixties, who basically invented the music that followed jazz). I did study a little bit of South Indian classical and folk music when I was an undergraduate, and that music is based on the raga structure which is melodic. So much of that music has a drone in it, which is a sustained pitch or a root, and everything else goes off that, but is always related to that tone. It’s a good metaphor for a lot of other activities that we could be engaged in. There is a bass/base. There is a foundation. There is a drone and that tone is coloring the rest of the sound we hear. And on top of that there is quite a bit of freedom to do whatever. But it’s not totally free because it is always going to be rhyming or linked to that foundation. Like a tether. That’s what happens in a jazz standard with chord progressions. Once you’re in that chord, all the notes in that chord are playable. Then you shift to another chord. There are different notes that are sharp and flat in that chord so just singing along, there’s going to be agreement. And at a certain point everybody decides, we’re not searching for agreement, we’re not searching for harmony, we’re searching for something else. But I don’t want to get too technical. Most of what I know is from listening...

To shift to the visual, though, my piece an overtone (for M) is a really good example of what we’re talking about. It’s a found wooden frame with glass. I made the first marks on it and then was trying to do a controlled drip and the paint marker exploded. The blue on top was a bit of an accident, but like the most perfect accident that you could do.

Right! So then in your piece, you see you’ve got the structure, and then this kind of wild action of experimentation and journey that occurred within it, and from it, because of it—

Yes, because of it. I think in general that play and tension between a mark that is very rigid or a more formal hard edge thing always makes me feel like I need to complement it with something else—something that comes from the play or the practice. Well, maybe not always, but I’m into when that happens. I’d made an earlier body of work on glass plates and there were intentional marks on one side, and on the other side of the plate more of a pooling ink that could play in the negative space. overtone has that too, where there’s marks on both faces of the glazing, as well as on the wall behind. But I think having something foundational or rigid to experiment on top of is very much linked to my understanding of music.

I see that push and pull happening with the complements. So maybe you bounce off of one aspect and “play” its opposite or decide to “play” something harmonious.

I kept naming it “call and response,” which in music would be the soloist and the band or the singer and the chorus, or the audience, when you involve them. As an individual I make a move and then respond to that move, at a later time, with a delay. In my performances what I’ve gotten really excited about is using a loop pedal, which is really just a delay. It's a way to record a phrase and then play it back, and sing again on top of it. I like to accumulate lots of layers. This seemed like a very embodied logical next step for me. In my installations (I had three solo shows in 2017-2018) I had to consider the whole space now, and create an experience for someone else to walk into. It became clear that the space or the time of install was the chance to improvise the exhibition. It didn’t feel right to generate the work through such an improvised process and then disregard that entirely when it was time to hang the show. I needed to be in the space to feel it and hear it and let it affect me, which helps me figure out where and how things are experienced. Especially in the second and third shows (Sound Gestures and Refusal to Coalesce) the result was that I’m kind of asking you to improvise with me as you move through the exhibition.

…soon, 2018, acrylic, latex, embroidery floss on moving blanket, 70in x 82in

(foreground) Trust. Improvisation. Exchange. duet with Greta Hartenstein, 2018, limited edition off-set posters (11in x 17in) with rubber bands on custom plywood plinth with casters, 14in x 24in x 4in

Your works are so much about also a kind of pleasure in the journey of the making. We can look at a piece and almost replay the process, the action. Are your works recordings?

Like the traces of what happened? Some of them might be. I think that’s an interesting idea...

I can look at your piece and almost replay the process in my head. This happened and this happened… And while you aren’t there to show us, looking, we can see all these layers in time-- stacked actions/marks--so I almost wonder about that kind of sense of playing along.

I wonder if that’s because I‘m so process-oriented and less interested in imagining an object and then trying to make it. Working with found objects is fun because it involves an element that is outside of my control so my task is to listen and respond to them. For example ...soon is a painted moving blanket that acts like an acoustic absorber when it’s inside the gallery. Something that typically protects artworks from damage is performing a similarly useful task in the context of the exhibition (Sound Gestures), curtaining a corner of the space so a viewer can fit themselves behind it and have more of a private listening experience with the audio piece playing on speakers above. At first glance, though, it’s an unstretched abstract painting. Behind ...soon I also installed a looped video on a monitor, August Studio Movement Score, which represents one month of my daily movement practice as a simultaneous multi-channel grid. I really like the notion that in a sense all these works are recordings. I also think a lot about absorption. Maybe there are two different processes, the making is the recording, and then the exhibition and the installing, and the context that you give is like the mixing and the mastering?

The way you approach installation is also process-oriented as well. And you put a great deal of thought and care towards extending the concepts and ideas surrounding improvisation to the installation process. In your exhibition Refusal to Coalesce you returned every 2 weeks to rehang the show and for Sound Gestures you advocated for a longer install period. Do you think of installation as a continuation of the making of the pieces or is it a separate process of making?

A solo show is an opportunity to generate context around the pieces on view, or to propose an idea more broadly. These exhibitions became an occasion for me to improvise again, and ultimately to model that experience for a viewer. Getting a long enough install period has become absolutely necessary for me because I need to spend time in the exhibition space with the works. Creating an installation is perhaps a similarly-minded process, but I wouldn’t say it’s a continuation of the making. Most of the time, I’m looking at what’s happening in-between works because their arrangement is a way to create dialogue. I sometimes call these groupings ensembles.

For Sound Gestures, with additional time to install, I was able to frame out and build a short wall at the front of the gallery to create another corner, and make the exhibition space distinct from the hallway. Viewers were met initially with a large yellow wall painting and had to enter the space before the rest of the exhibition was visible. Because that first large work spilled onto the floor at an angle, it prompted their movement into the space at right, and their viewership became active. I also created a collaborative text that was free for visitors to take. The stack of offset posters (plus rubber bands) sat on a custom plinth with casters, which meant the writing also became active, mirroring the back and forth dialogue I’d shared with my co-author, Greta Hartenstein.

The idea for Refusal to Coalesce came directly out of the audio collage I created for Sound Gestures, which quotes poet and theorist Fred Moten’s text “Blackness and Poetry.” The lines I spent the most time with seemed to speak directly to my process and the ways in which music is everywhere in my thinking. I loved imagining an exhibition that wouldn’t sit still. I conceived of the show as a performance score, but instead of a performer interpreting prompts or notation, I had the works perform. I installed the show and returned every two weeks to shift several pieces, making subtle changes so the exhibition itself was changing over time.

Refusal to Coalesce, 2018, installation with wall painting, framed print, neon tube and transformer, hand-woven textile, and painted works on paper, fabric, wood and plexi glass, dimensions variable

In the installation process, you also give a lot of consideration to the experience of the viewer. In the making of the pieces there’s a call-and-response between you and the piece. In the installation, the call-and-response is between you and an audience. When thinking about an audience is that audience singular or plural? Is it for the individual?

Yes, I’m making an experience for a viewer and that viewer is somehow always singular. I find that with writing, too. I’m imagining an individual reader. That’s why, at least thus far, I’ve really enjoyed making shows in small spaces. That first show (a score to keep time/a score to lose time/but never yourself, in it at the artist-run Sadie Halie Projects in Minneapolis, MN in 2017) was in a freestanding garage. I take seriously that I’m responsible now for everything that someone might encounter in the whole space because it’s a solo show. It means every decision is more important, but also that I can get deeper and more layered. Each work can do its own thing and the sum is the place where meaning is made. I also think it’s why I always want to throw a bright color on the wall, the sense being that I need to make the space mine. I can’t have the same white walls that I walked into when I started.

As artists we necessarily consider color’s sensorial potential—its optical effects, its depictive potential, and its perceptual capabilities. In my own work, I also think about color as a poetic element, a metaphor, that can be “amped” up or down and can speak towards a kind of speaking out or a silencing. Color can be emotive and referential, generous and aggressive. You also have a strong relationship to color. You are thoughtful in not only how it functions within a given piece, but also as an element in installation and exhibition. Can you talk a bit about how you think about and approach color? How does it operate within your works and in the exhibition of your works?

I believe color has a charge, an energy. I totally agree, color is poetry. For me it’s similarly intuitive, like music. There’s definitely a sense of resonance and register, and color can elicit an emotional response. Decisions come to me and I don’t typically second guess them. Initially my use of bright colors and wall painting in particular felt like a necessary gesture to refuse the white cube or the gallery space as neutral. When I make an exhibition, that’s usually the first move I make when I’m installing the show. It colors the rest of the space right away and gives me something to play off of. In some installations it was important to thread a certain color through various pieces, but in others, I was more interested in bouncing off, introducing a tone that was not seemingly present anywhere, and making the installation a whole consisting of different, but interrelated parts. I love that notion of interdependence and interconnectivity. I also feel like my use of bold colors was a new way into the kinds of critical conversations I wanted to have. What about joy? Or pleasure? I was tired of the assumption that “serious” work should be bland or monotone.

Color is not thought of as intellectual, right?

Right! It’s not serious, it’s not academic, it can’t engage the more important subjects like politics or society. It gets labelled decorative or gratuitous or emotive or brash. I think there’s a high/low culture debate and a critique of accessibility embedded here. There’s a Howardena Pindell quote that I love. I encountered it at her retrospective at the MCA a few years ago, she’s responding to gendered limitations on artistic practice: “Glitter. Pink. That was my way of resisting.” Her shaped abstract paintings are full of materials and palettes that would have been dismissed as feminine, and therefore not serious, but she’s engaged in a really rigorous kind of formalism.

undersong (for audre), 2019, crayon and liquid watercolor on 18 sheets of Canson cold press notebook paper, 12in x 9in, each

Your work also considers and carries resistance--a kind of resistance to despair, a call to the right to humanize others and the self, a call to care and carry forward. Your work takes a strategy developed to survive and transforms it into a nurturing, creative, connective force of expression. Is resistance always legible in the context it occurs and to whom? Is it often dismissed and by whom? Does working abstractly further compound the challenges around the legibility of resistance? How are some ways you have created access points around your work?

Thank you, that’s so generous. Something that’s been equally important in my life for the last five years has been writing. It’s intimately connected to my visual work, not secondary or explanatory, and I’ve come to see it as another medium to express and explore these ideas. I think once I was working more abstractly, language became a significant counterbalance. I write mantras, or life-scores, to guide my research or focus an intention. One of the first ones was handwritten on the wall of a temporary studio I was working in at the time, [allowance to play, language comes later, let it emerge, permission to not know.]

I think writing can absolutely be another entry point for viewers, but I love the openness of abstraction, it’s never trying to tell you what something is, whatever someone sees in the work is there for them in that moment. I think of legibility more in terms of creating an experience that is accessible and not, let’s say, ensuring a particular outcome or understanding is reached. In general, the viewer/reader who engages in a deeper way will get a more robust feeling from my work, but I don’t want to force an interaction that’s not wanted. My texts are often printed as giveaway posters and placed inside the installation with the same care as the artworks. It feels good to physicalize the words in that way, and to offer something folks can linger with after they’ve left the gallery. I’ve also written stand-alone texts, and my most recent poetic essay feels directly in line with what you say above.

From April to June 2020, sheltered-in-place in my Harlem apartment, I wrote about the twin crises of the global pandemic and police brutality. “we must be very strong/and love each other/in order to go on living” includes personal reflections of the changing seasons and accounts of protests I attend or witness in my neighborhood. It charts my experiences as they unfold in real time over the first few months of our new reality. Commissioned for The Laundromat Project’s Creative Action Fund digital initiative, the piece lives online as a minimally-formatted webpage, with audio of me reading it. I wanted to make it more embodied, and it felt important to say these words with my voice and offer that intimacy into the maelstrom of the internet right now. The title is inspired by the last lines of an Audre Lorde poem (Equinox, 1969). Her work reminds me that caring for ourselves is a (political) necessity. It’s an honor to work again with The Laundromat Project, I was part of the first cohort of the fellowship program almost 10 years ago. Their work has helped shape my understanding of what a community and values-driven (art) practice can be/do. You can read or listen to my piece at http://bit.ly/wemustbestrong

It seems at times almost as if your artworks are the crystallized moments or intersections of surrounding processes and intentions. They act as visible nodal points for the invisible supporting thought, experience, support, and labor--like stars in constellations. Do you feel like working through the lens of improvisation has allowed you to work and think in a broader, more expansive way?

Absolutely, that’s a great observation. Once I had the language of improvisation, once I noticed it was a framework that could hold all these other layers and concerns, it became such a valuable teacher. When I am open to all of the possibilities, not looking for a familiar or expected end result, I give myself permission to try or play in a different way. In the process, I’m expanding the scope of my work. I started moving away from what was comfortable or from what I was sure I could do well, and started asking more open-ended questions, like “what if?” This pushed me to study improvisation in a broader sense, too. My research methods became more embodied. I signed up for dance classes and learned to weave on a floor loom. It felt super important to put myself in new creative environments, to practice something I had no prior training in. This was invigorating and generative; I could feel it expand my thinking. I love learning new things and being challenged by them. It’s a vulnerable place at first, of course, but it’s also incredibly exciting because you realize you’re searching for some kind of feeling you don’t have words for yet. You have to be patient. I was reaching out constantly towards the unknown. Weaving is always the best metaphor here. The floor loom requires so much time and labor to set up. You have to wind your warp, thread each end through the heddles (the up-down mechanism you control with foot pedals to generate your pattern) and again through the reed at the front. On my larger pieces, like blue nile (for alice) which has 400+ ends, this process can take up to 25-30 hours of focused attention. Once you’ve prepped the loom and are finally ready to weave, you grab your weft and you can really fly; it’s so fast! I love this part because it’s physical and intuitive. I can change colors quickly, or grab the EL wires and work those through as a third axis, but this fun part is only possible because of the preparation. That slow behind-the-scenes work is the foundational support for what we see in the finished piece. The labor, both physical and intellectual, that happens in the studio creates the conditions for everything else we build on top. Improvisation encompasses the rehearsal time and the spontaneous performance.

I like this idea of nodal points. Moving between mediums and materials gives me the opportunity to pull out different aspects of my thinking. Installations are encouraging because each work doesn’t have to do everything, the constellation or the ensemble or the chorus can say something collectively, right? Also, back to the idea of recordings, a good friend (who is a performance curator and a dancer) once reminded me, “not all work leaves the studio.” I say this to myself often, it’s such a good reminder. Sometimes you make work because you need to see it. The process of creating an exhibition is a different one, you’re an editor or an engineer, perhaps you’re only showing the best takes, or the ones that work most successfully together.

I like how you talk about improvisation from the point of listening and collaboration. These are values and processes that are often associated with caretaking and the feminine. But I also want to say, particularly, listening and collaboration under the scope of a readiness/preparedness, seems a landscape that Black womxn in particular have had to occupy and take lead on.

Yes, that was an early observation of mine. Instead of only paying attention to the competitive one-upmanship aspects of improvisation as virtuosity, I started looking at the capacities for collective achievement that necessarily require a mode of working together for success. Put another way, if no one is listening to each other, the loudest person takes up the most space, so whose voices are we never hearing? Of course, there is a long history of collaborative struggles for justice, and more often than not, there has been an understanding that caretaking is crucial for the continuation of society, or social reproduction, but that work is both essential and gendered so it is largely un(der)paid, undervalued or erased altogether when patriarchy gets control of the narrative.

I’ve taken particular refuge recently in the Combahee River Collective Statement, which is reprinted in How We Get Free edited by Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor. The group’s fundamental analysis was: “If Black women were free, it would mean that everyone else would have to be free, since our freedom would necessitate the destruction of all the systems of oppression.” It’s an expansive liberatory framework. Other outstanding texts on constant rotation are: Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds by adrienne maree brown (thank you Jennifer Harge for putting me on), Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval by Saidiya Hartman, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being by Christina Sharpe, and whatever I can get my hands on by Audre Lorde, Octavia Butler and Angela Davis. All this to say, my reading of improvisation is deeply informed by the ongoing critical work being done by Black womxn and it feels important to name just a few of these thinkers here. I’m also learning more about disability justice and decolonization, and am inspired daily by the folks organizing mutual aid efforts and free food programs in their neighborhoods right now (love to Public Assistants and Crenshaw Dairy Mart, especially). These practices have radical historical roots, and I always feel emboldened when I can place myself within a lineage and a conversation.

There’s a term I keep coming back to, “collaborative survival,” from The Mushroom at the End of the World by anthropologist Anna L. Tsing (shouts to iris yirei hu for recommending it a few years ago). Among other things, Tsing unpacks that particular myth of rugged individualism that is so insidious in (white supremacist patriarchal) American culture. The idea that we’re not connected to anyone else or that obligations we keep to others make us weaker is a LIE that perpetuates the kind of greed and violence and hoarding we see now. It’s not new but it’s extreme. adrienne maree brown writes poetically about adaptation, interdependence and pleasure, and these ideas resonate with and reaffirm my conception of improvisation, which guides not only how I work in the studio and the exhibition space, but why what I believe matters out in the world. It’s empowering to recognize that something like improvisation, a capacity we all have to negotiate and navigate the systems we find ourselves in, can be one way to cultivate and nurture the parts of ourselves that are most needed to ensure a just future.

How you think of freedom is, I want to say, a more considered freedom. I think about “freedom to” and “freedom from,” and in order to have the “freedom to” act or do, you have to have the “freedom from” say, basic threats to security. Can you talk more about your work in relation to freedom?

I think we often have a difficult time defining freedom without necessarily referencing whatever we imagine to be unfree. Our definition of a free person generally just means that they’re not in prison. Free improvisation in a movement setting is usually without choreography. It’s always relational. A few years ago I had the opportunity to practice “authentic movement,” which is a partner exercise where one person has their eyes closed and is supposed to move however they feel inspired to. No judgement, no thinking (it reminds me of Quaker silent meetings), you just feel called and you do the thing. The second person is the witness and is charged with keeping the mover safe. When the mover opens their eyes at the end of the 5 minutes, the witness holds space for them. Or, in one variation, the witness tries to give back a gesture the mover gave them. The context was a room full of white people and I got paired up with the only other Black woman in the group, and we noticed people kept saying freedom, but we asked ourselves, what do they mean? We might all mean something different. So we came up with this phrase that became our movement score, and eventually one of my mantras (it ended up as handwritten text in the evolving wall drawing in Refusal to Coalesce) [put freedom in context].

Freedom to do anything already necessarily assumes a baseline level of safety. We can’t assume this for the segment of the population dealing with ICE or the police. By design, police were created to return runaway human property and to assure a base level of safety for those wealthy white male citizens whose property had escaped. In order to think expansively about your life or the freedom to imagine something you’ve never seen, you must already have your basic needs met, your housing figured out, enough food, health and mental/spiritual well-being, adequate rest...

So the problem that I encountered with some of that freedom discourse, especially around improvisation, is that it assumes a similar level of freedom for everybody. The real working definition of improvisation that I came to was that it’s an awareness of a limitation, and then it’s a moving through that. That’s where it becomes legible. Essentially we’re working with a given limitation at all times anyway. Your instrument can only go so high. Your body can only do so much physically. It shouldn’t be about eradicating difference or trying to get to some kind of a false equality, but it’s an awareness of the structure or limitation or boundary. You only ever have the space or time or tools you have. In the audio collage I created for Sound Gestures I sampled a favorite song of mine by Deniece Williams, who sings, “I just want to be free. I just got to be me.”

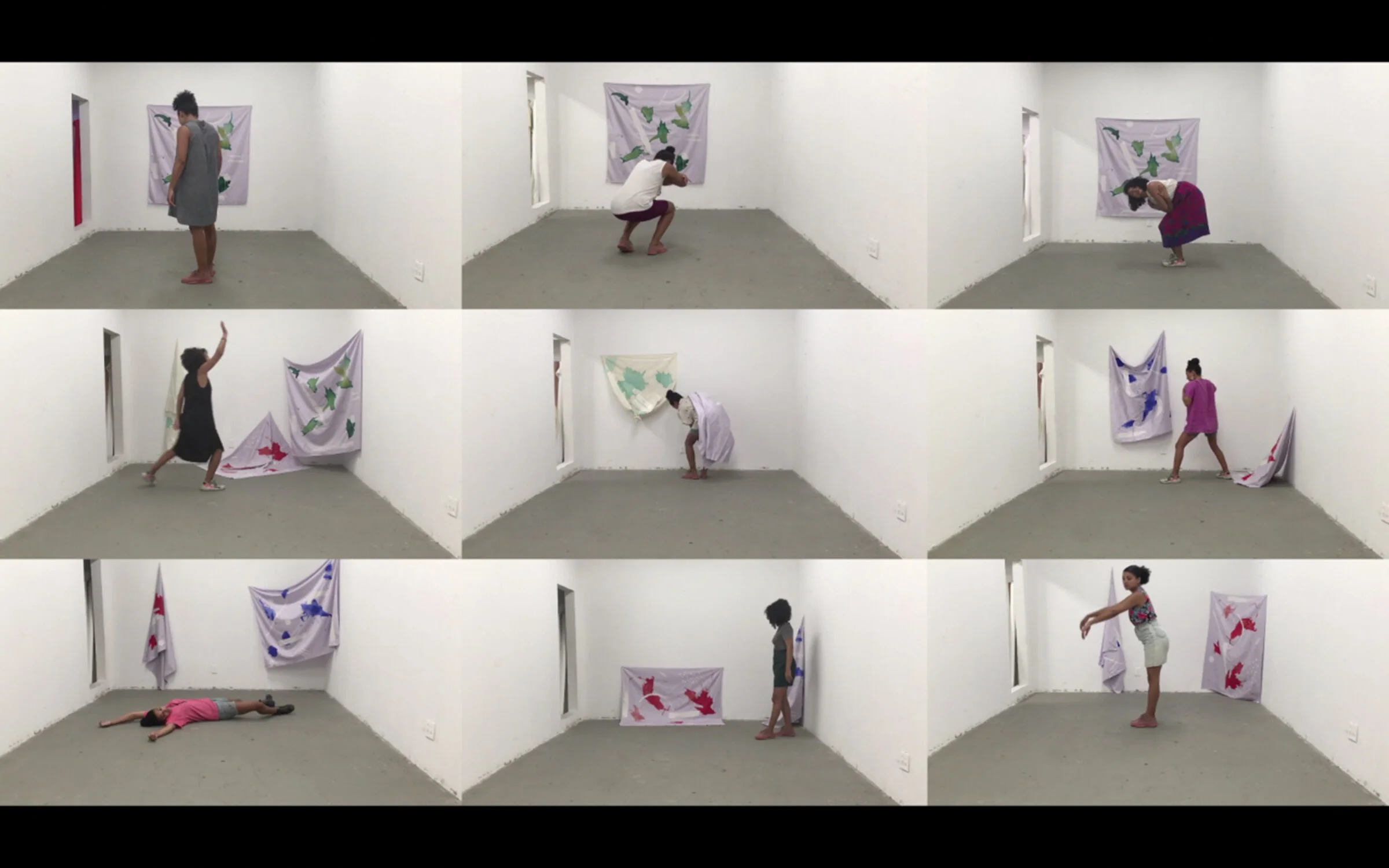

(still) August Studio Movement Score, 2017, 9-channel video, silent, 4 minutes 45 seconds

Do you think that it is in meeting a boundary or an edge, it is at that point at which you discover your resources and your limitations, and how to surpass them? Do you think you only understand that when you hit that edge?

Maybe...and maybe that’s when you give yourself permission. Because you say, I have studied. I have trained. I know myself. I can overcome this. Maybe the edge was something self-defined that said I can’t make that kind of art. I didn’t go to school for that. Or I’m not allowed to speak about this issue because I haven’t read enough to talk about it. Or I can’t make something so colorful or exuberant because art is supposed to be boring and white. You know? Maybe the edge is always the thing that you’re confronting and you make the work to get around it.

And in doing so, your world gets bigger and bigger, and bigger. Because the edge moves out.

Yes, absolutely. And when I’m improvising and I’m in that space, that zone that we can’t quite talk about because it’s not articulable, there’s an openness and an expansiveness that is palpable. My awareness shifts. I can hear differently. It’s an abundance mindset, instead of a scarcity mindset.

What new environments/new practices have you been immersing yourself in lately? What have you been working on and thinking about in your studio? What upcoming projects are you excited about?

I’ve been working with an industrial rug-tufting machine for about a year and I’m really enjoying it. I lost access to my studio at the end of March, but I was able to grab some yarns and relocate to my bedroom. I’ve really been trying to move slowly and focus on setting up healthy boundaries because it’s such a heavy time. In March 2021 I’m releasing a book of writing spanning the last five years of my practice. The first part of the title is inspired by another one of my mantras, which has been especially resonant now in the midst of the uprisings, “slow and soft and righteous, improvising at the end of the world (and how we make a new one).” The tufted works are getting at that middle section of the mantra, and I’m thinking a lot about how softness calls for a different kind of response to the harshness and violence of our society. Since a lot of my texts were written as individual posters, I’m super excited to see everything together for the first time. It’s going to be printed on a risograph and published by the incredible Co—Conspirator Press, which operates out of the Women’s Center for Creative Work (WCCW) in LA. Hopefully, I’ll get to do a mini-book tour, or at the very least, some exciting online conversations to celebrate. Keep an eye out! Lastly, I can’t help but speak about the truly terrible times we are living through, which are not unprecedented, but are exacerbated by the very calculated and also totally improvised moves our current administration has made. I would be remiss not to mention that improvisation can have truly disastrous effects, and I don’t believe it’s synonymous with good intention. Something that’s kept me going these last six months (aside from already-remote employment and my material needs met) is being both super present and making an effort to dream for the future. I feel like I have a handle on my analysis of why things are awful, but it’s so important to practice visioning, and for me personally, it’s a better space to be in than constant rage. I have an ongoing speculative project called Become Together Freedom School that I began a few years ago as part of my Culture Push Fellowship for Utopian Practice. My project’s been dormant recently, but I’m feeling called to re-activate it now, perhaps as a series of virtual gatherings and intentional conversations with like-minded folks. I’m definitely being challenged to re-imagine what togetherness means now, but I always learn so much from talking and I think I’m finally ready to accept the internet as a space of connection if/when we engage thoughtfully (it’s not perfect). Thanks for speaking with me Nancy, it’s been a true pleasure to be in dialogue with you!

And thank you, Sonia, for being so generous with your thoughts and motivation surrounding your work. Your approach towards making as a means of expression, connection, and care is very much welcome during these troubled times. We look forward to reading your upcoming publications and experiencing your latest pieces!