Sean Downey

These paintings try to imagine the underlying circumstances of an image’s origin. In much of the work cinematography serves as a visual metaphor for the machinery of image production and its relation to lived experience. The slow, analog, clunky language of painting becomes a way to both resist and revel in our own contemporary condition of nonstop image production, with an understanding that the painting studio is also a kind of machine that generates images.

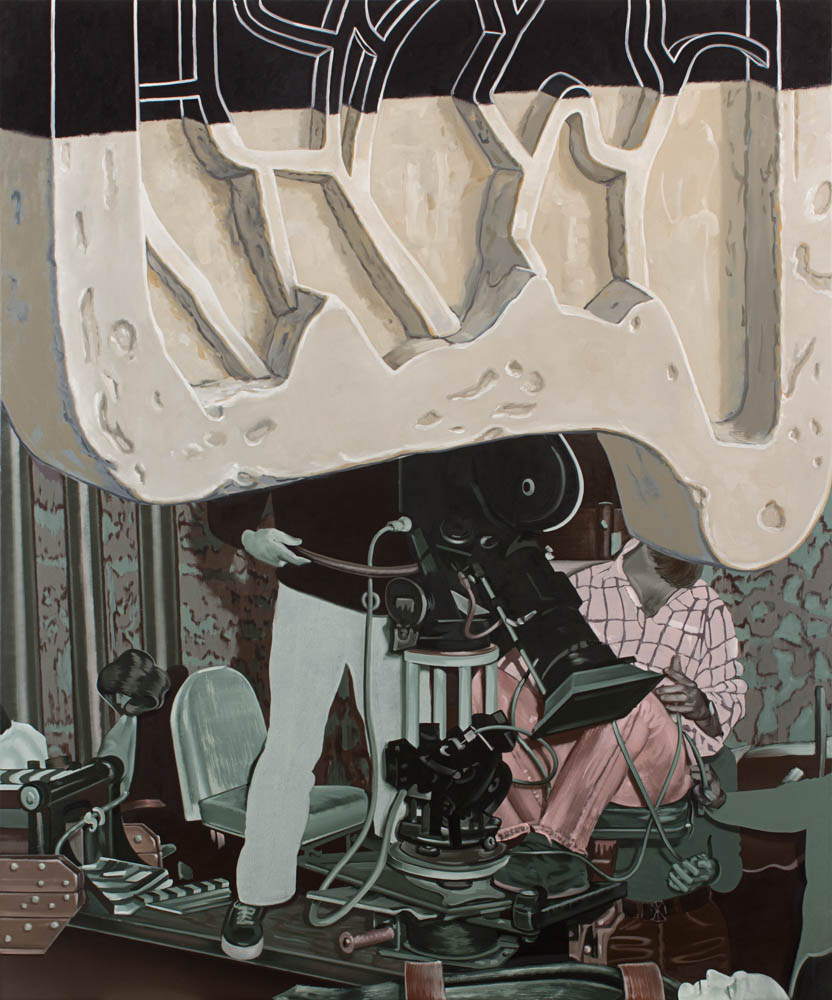

Sean at work in his studio.

Interview with Sean Downey

Questions by Beatrice Helman

Hi Sean! Thank you so much for talking to us. How did you first become interested in painting and how have you seen your relationship to the act of painting change over time?

I think I can point to two early art encounters that really locked me into painting. The first was being taken to an art gallery in Seattle in the third grade and seeing Jacob Lawrence’s poster for the 1972 Munich Olympics. It blew my little mind, the way the running figures were bending around the track—I still think about that image all the time. The second experience was in high school, on a field trip to MoMA, seeing a Franz Kline painting. It was the first time I really felt floored by a non-representational painting, and that same whatever-it-was seemed to be coming out of all of his work. I couldn’t really make sense of it at the time, but I bought a monograph on him and brought it back to the small town in eastern WA where I lived. I spent a lot of hours staring at the reproductions and trying to figure out what was going on in those paintings, and why they were so good. Around that time I also discovered Rauschenberg, and from then on being in the studio and trying to sort through this stuff was basically the only thing I wanted to do all day every day. The most profound thing that encountering those artists did for me—and this was also nurtured by a lot of good teachers later on—was to break down any distinctions I had between representational and non-representational, and even between painting, sculpture, or any other medium. For me the only real reason I’ve consistently returned to a pretty ‘traditional’ relationship to painting (I also occasionally branch out into sculpture and ceramics) is that I have found that having some restrictions on my studio practice is actually very liberating in a lot of ways. Painting seems to work pretty well for getting at a lot of the things that I’m interested in, and in conceding that aspect of the form of my work I’m trying to open up a path to hopefully get into some of the subtler, less language-based aspects of the content. Also I feel like I haven’t hit the bottom of painting yet—it keeps just going down and down, and seems to always be revealing new things.

What are some of the resources and things that have inspired you over the years—and this series of paintings in particular?

Films, historical texts, and other artworks are resources that I constantly return to. I’ve spent a lot of my life working in libraries, museums, and archives, and it’s left me with this overwhelming sense that there are a ton of amazing gems hidden in dusty, obscure corners that have been overlooked (just the word ‘archive’ makes my heart beat a little faster). Of course obscureness is not the important thing, but more the idea that history and the objects that it has produced are very much alive and speaking to us in the present.

For these paintings I was reading a lot about the revolution in popular perception that happened in the late 19th/early 20th century with the proliferation of photography and film, and thinking about what parallels that time might have to our own time, which is undergoing a similarly profound revolution in how we make and proliferate images. Additionally, I was thinking a lot about my own place as an image maker within this historical moment. A lot of the sources come from looking at old black and white film production stills. I got interested in all of the clunky, provisional scaffolding and wonky constructions that were used to hoist heavy camera and lighting equipment to get a specific shot. The images of these weirdo structures also felt very familiar—as a painter I’m always building provisional setups and devices to get a painting to do something specific. And as an artist, I’m extremely aware of how much my process and my setup influence the work that comes out at the other end. This is also why I love seeing other artist’s studios, and what setups they’ve constructed to make their studios do what they need them to. So I wanted to make paintings that had a figure, drama, or scenario as a ‘subject,’ but seemed to be as much, or more, about the compositional structures that were ‘delivering’ the subject.

How much does your current location and your surroundings show up in your work, whether it be subconscious or conscious? I know that you’re based in Boston right now, which is where I grew up, so I’m always curious as to how it might play into someone’s work.

I lived in the Bay Area before moving to the East Coast, and more than any other place that location had a tendency to make its way into my work. I was constantly outside when I lived there, drawing and gathering imagery that I would take back to my studio to construct paintings. Not so much in Boston. The only two definite location-specific things that I can point to that have shown up in my work here are wainscoting and Walden Pond. It’s funny you should ask though, because it’s definitely on my mind right now. After more than ten years in Boston, my family and I are preparing to move to a small town in Iowa later this summer. My wife (also a painter) and I have both mostly only lived in large cities, and we’re very curious to find out what (if any) impact such a huge geographical/cultural shift will have on our work.

I’ve heard you described as, and would also describe you as, a surrealist painter, and I’m wondering how do you personally define surrealism? Do you see it in your own work, and would you identify yourself as a surrealist painter?

Well, my knee-jerk reaction is to strongly resist an identification like that, mainly because I tend to think of Surrealism as an art-historical identifier that’s pointing to a specific period in the 20th century. That said, as a painter that uses representational imagery to try to talk about the way we process images internally, there is definitely a relationship to some of the Surrealists’ intentions. But still, I think of the term itself as retrospective; I’ve never started a painting with the intention to make something surreal.

Do you paint from sourced images, from images taken from daily life, or completely made up scenarios? Where do you find inspiration for the content of your paintings and the worlds you create?

All of the above: film stills, found images, drawings, collages, still life setups, friends posed in costumes, etc. Usually I start from pretty clear sources, and then once the painting is up and running I stop referring to sources and try to let it go it’s own way.

How do you begin a piece? Do you plan the structure ahead of time, or let it unfold as you work? The paintings seem to be constructed in such a way that the structure almost becomes its own narrative.

Yes! “Structure as narrative” is very much how I think of what I’m after. The way I get to that has changed over time. I used to do a lot more of just jumping into paintings with only a very vague idea of what I wanted, and that usually meant that nearly all of the paintings got painted and repainted over and over, and went through a bunch of really drastic changes before they were finished. A few things changed that approach for me. The first was that in looking over process shots of my older paintings, I could see that interesting things were popping up that my bulldozer approach to painting was crushing before they got a chance to really be investigated. The second thing that happened was that some of the paintings I started wanting to make were just not the sort of paintings that would ever happen by accident, like as just the accumulated sum of a bunch of spontaneous painting activity. They needed planning and follow-through. Finally, one of the biggest changes that has affected how I make paintings has been having a child. It’s made my studio time feel much more high-stakes. These days I don’t change the direction of a painting just to change it, I’m much more likely to follow an idea through to the end rather than spending all day noodling through tangents.

Can you talk about the use of juxtaposition in your work? I feel like your paintings contain images that are purposefully disjointed in such a way that they’re actually connected. How do you go about working on each piece separately while also keeping in mind the aesthetic whole?

I think of the imagery I use in pretty abstract terms. I think of recognizability of imagery, and narrative, as just additional dimensions of pictorial space—like light, color, value, etc. I have a pretty collage-minded approach to creating images; I’m constantly returning to the idea of taking ‘known’ components and combining them in such a way that something new and strange emerges, an idea or mood or reference that was not previously in any of the component parts, but only emerges if they are assembled in a very specific relationship to each other. The language of painting is the place where I can unify those disparate parts (or ideas), and then meter how disjointed or fluid things are. And for my own work I’m only really interested in what happens once images pass through the medium of painting or drawing; I’ve never really just made collages for their own sake, or even taken photographs for their own sake. I have to paint or draw my way through an image to understand it. Something about the time it takes to create an image from scratch, with brush and paint, and how that time gets embedded in the painting, seems to be really important.

I felt like there was a lot of humor in this collection of work, and in your work in general, particularly in Cookie and Love. What is your relationship to humor in your work, and is that an intentional choice?

I’m glad to hear that the humor is apparent--it’s certainly something I want in the work. I don’t think the paintings are ‘funny’ exactly, but I’m after an undercurrent of visual humor; like the underlying structure of a joke, where you set up a kind of contained context that establishes certain expectations, and then you insert elements that subvert or contradict those expectations.

I recently read an interview in which you talked about this idea of dropping into a narrative, such as starting a book halfway through. Can you elaborate on this?

The idea comes from a text by Kierkegaard, called The Rotation Method. He talks about using arbitrary variables to subvert what might otherwise be an overly dictated or predetermined experience. I think it’s especially relevant right now, when we have all of these online algorithms trying to predict and curate for us. But I also think it’s an inherent and unavoidable quality of a lot of art-making and art-viewing. When you encounter a new work or artist, you’re always dropping into a new context and trying to locate what is going on in that world, and in that attempt to locate you’re always creating new, unintended meanings for the work. I’m really averse to the idea that artwork needs to remain tethered to the intentions of the person who made it.

Are there any themes or concepts (or feelings) that you keep returning to, or have been returning to continually over time?

I think I continually return to the theme, or feeling, of the associative way that we experience the world: the way that you can be having an experience and simultaneously be remembering previous experiences and imagining future experiences; the way that all of these connected and disconnected projections get layered over all of our experiences.

You mentioned, “The slow, analog, clunky language of painting becomes a way to both resist and revel in our own contemporary condition of nonstop image production, with an understanding that the painting studio is also a kind of machine that generates images.” Could you explain a little bit more what you mean by that?

When I was doing all of this reading about the history of cinema and photography, I started to have the feeling that my studio was like the inside of a polaroid camera or something, like a box that was periodically ejecting images into the world. And in this time where there’s a constant stream of images washing over us all of the time, I felt like painting could be a way to pay tribute to an image, to take the time to be with an image for a while, to sort of resist the motion of scrolling through.

What is your relationship to social media? Do you see it as harmful, helpful, a work tool, a distraction?

I’m really grateful that there is a platform like Instagram, at least in its current form. I’m sure someday soon Instagram will go the way of Facebook and just become a trash heap of bots, clickbait, and life-event notifiers—but for now I think it’s great. I mostly only follow other artists and galleries. I know there are a lot of bad things about it, but I really like seeing what other people are working on, and learning about new venues, artists, and publications (I’m pretty sure I first heard about Maake through Instagram). I also like that I don’t have to live in the same city (or country) as another artist to know their work, or wait for their work to be vetted and presented in a gallery setting. I also find that it makes it harder to make big pronouncements about the ‘state of the art world’ when you’re constantly seeing so much variety and great new work being made all the time. Before social media, I might see a really bad or good round of shows in Chelsea and start drawing some hyperbolic conclusions from that experience about the general state of things. Now I’m always very aware that there are a bunch of really great artists chugging along out there all the time. I think social media has also hugely bolstered the ‘artist-run’ part of the ecosystem. Artist-run spaces and publications can exist online in a way that they become legitimized more by what they are presenting as opposed to where they are presenting it. I love it that you can do some amazing thing in a DIY venue in some random city, and it has the potential to not only serve the community where it happens, but also to have this expansive other life in dialogue with everything else that’s going on out there. I know that’s probably a pretty naive take on things with regards to the larger market forces, but I’m more interested in ideas and how ideas get circulated among artists.

What are you reading, eating, watching, or listening to right now?

Reading: American Colossus by H.W. Brands, and Duty-Free Art by Hito Steyerl

Eating: Dad stuff, like super healthy smoothies and homemade pizza and crafty beer

Listening: Arthur Russell, Kevin Ayers, Aldous Harding, Cass McCombs, Karen Dalton...

What do you do when you need a break and have to let off steam?

The usual stuff like watch tv and drink with friends. I’ve also been meditating regularly for a few decades, which is like a low-key daily steam let-off.

Who are some other artists who you look to and admire at the moment?

Tough question, so many people are making great work right now! Recently I’ve been really floored by Natalie Frank’s work. There aren’t too many people that have the chops to do all of the things she does in her work and make it all come together in such a beautiful/ugly/rich/punchy way. I was also really blown away by the recent Mernet Larsen show at James Cohan, and the Zurbarán show at the Frick. And then I’m always looking at Manet and Degas. I’ll forget about them for a few months and then see something in a museum or book and fall in love all over again.

Do you have any projects, shows, or residencies coming up?

Some things in the works, but nothing to announce just yet!

Thank you so much for talking with us!

To find out more about Sean and his work, check out his website.