Millee Tibbs

Millee Tibbs’ work derives from her interest in photography’s ubiquity in contemporary culture and the tension between its truth-value and inherent manipulation of reality. Tibbs’ exhibition venues include the Blue Sky Gallery – Oregon Center for the Photographic Arts, Portland, OR; the Museum of Photographic Arts, San Diego, CA; Mary Ryan Gallery, NYC, NY; the DeCordova Sculpture Park and Museum, Licoln, MA; Brown University, Providence, RI; and Notre Dame University, IN. Her work has been published by the Humble Arts Foundation, Blue Sky Gallery, and Afterimage: The Journal of Media Arts and Cultural Criticism. Tibbs’ work is in the permanent collections of the RISD Museum, the Portland Art Museum, and Fidelity Investments, and is also held in the Midwestern Photography Project at the Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago, and in the Pierogi 2000, Brooklyn flat file. She has been awarded residencies at the MacDowell Colony, VCCA, Jentel, the Santa Fe Art Institute, and LPEP, Buenos Aires, Argentina. Tibbs grew up in Alabama, completed an MFA at RISD in 2007, and is an assistant professor of photography at Wayne State University.

Statement

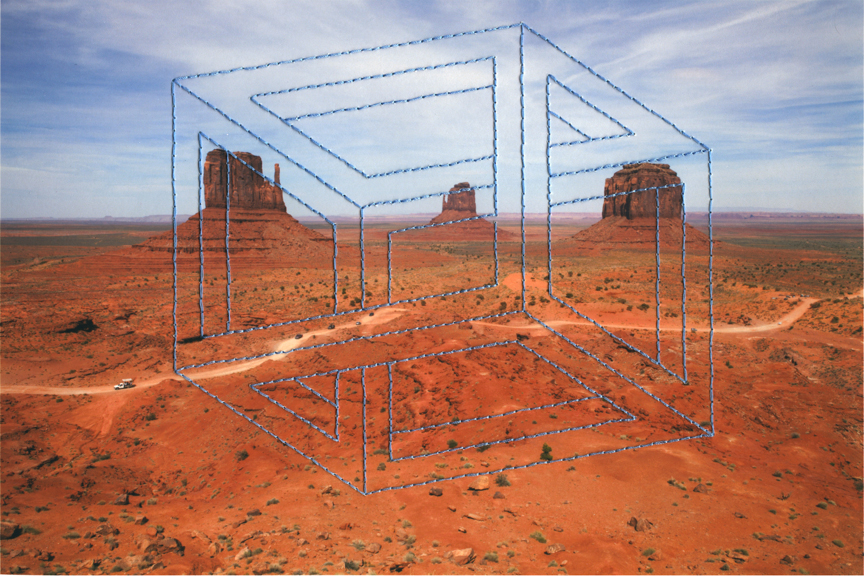

My work addresses the fabrication of a romanticized ideal of the American West through the propagation of landscape imagery that glorifies a vacant wilderness. I am interested in the dichotomy between “landscape” (an intangible vista) and “place” (a tactile, inhabitable space). I use images of the American West as a starting point to interpret and confront patriotic myths that are disseminated through the representation of that landscape. This vision of the land has been used to express patriotic ideals of Americaness – rugged individualism, expansionism, Romantic Nationalism, and Manifest Destiny. I focus on the aesthetic framing of this landscape that perpetuates expansionist ideologies through the representation of unoccupied, and seemingly unoccupiable spaces. My work is informed by the history of photographs of the American West and their relationship to the visual language that preceded them.

Like the works of the Hudson River and Rocky Mountains School painters, early photographers employed the sublime to fulfill moralistic and political ends. Dramatic vistas of inaccessible, uninhabited landscapes became the visual codes that define the genre. By disrupting the photographic image through physical interventions (folding, cutting, and sewing), my work responds to the miniaturization and domestication of the land through photography: each image holds the tension between the expansive, inaccessible vista and the intimate, tactile experience of the photo-object.

Q&A with Millee Tibbs

by Emily Burns

When I first saw your work, I imagined your work as dimensional objects, but upon further investigation I began to wonder if the finished works were photographs of the manipulated photos—making the final work flat. This is one of the downsides of viewing work online! Can you describe how the final work exists in a gallery setting?

I know, presenting the documentation of this work is really confusing. The final pieces are photographs of physically manipulated photographs. All the pieces are flat and are framed. Even so, the work seems to have dimensionality which continues this visual confusion onto the gallery wall.

Are you the original photographer of the images of the landscape or are these appropriated images? Does this matter to you?

Yes, I made the original photographs. It matters to me for two reasons. First, I get the chance to travel to these places. I love the outdoors and long road trips, so taking the pictures is a lot of fun for me. Second, it is important to me to experience these places. So many of the iconic images of the West make the landscape seem uninhabited and desolate. Most of these places are anything but. I am usually surrounded by hundreds of tourists when I make these pictures. I am fascinated by the discrepancy between the decontextualized image and the experience that made it.

The images are distinctly reminiscent of those that propagated the romanticized ideal of the American West that you mention in your statement. Can you describe some of the characteristics or elements that are important to this representation?

The language of genre landscape photography is informed by early American landscape painting and use the same tropes: uninhabited spaces, high vantage points that dislocate the viewer, bright colors, and dramatic skies. What is interesting about the iconic images of the West is how easy it is to access those vistas. Most are pretty well developed "scenic view points." In fact, many include placards that show iconic images of the same landscape—as if experiencing the view is not enough, one has to be shown how to view it.

Can you talk more about the miniaturization that occurs when looking at scenery or locations as photographs?

The world is big—photographs are small. When we photograph a landscape, we shrink it to fit onto the paper or into the screen. It also becomes metaphorically smaller—a souvenir that can be carried away. Repeatedly framing and decontextualizing these places through photography increases their aesthetic appeal, but diminishes the complexity of their historic meaning.

I am very interested in the idea of expressions that glorify and idealize, across a range of subject matter. What drew you to the landscape of the American West as an entry point for this discussion specifically?

Before making work about the landscape, I was very interested in cliché and snapshot photography—how vernacular images can have such acutely personal meanings, but how generic the images themselves are.

I think it was this element of cliché inherent to the genre of landscape photography that piqued my interest. In 2010, I attended an artist residency in Santa Fe, New Mexico. It was the first time I spent significant time in the American West and I found myself thoroughly seduced by the landscape. In an attempt to bridge this seduction with a more informed response to the iconography of western landscape I made two bodies of work ("Virgin Land" and "Virgin Land, Wyoming") that paralleled the symbolism of the unicorn to the mythology of the American West. My subsequent work deals more specifically with the aesthetic framing of the landscape itself, but continues to be informed by my interest in the cliché and how it can be a vessel for political agendas that promote manifest destiny, expansionism, American exceptionalism, etc.

What drew you to photography as a medium originally? What interests you most at this point in your career?

Initially, I think it was the subtractive nature of photography that drew me to the medium. You start off with the world and then through a series of decisions (framing and timing) you choose your photograph. I don't think I ever liked starting with a blank page... Now, I am much more interested in photography as the most prevalent form of visual language. It is ubiquitous and has become fundamental to so much of our social exchange. Despite its apparent "transparency" it is rife with codes and conventions that inform its reading. I am fascinated with how pluralistic its uses are and how much the act of photographing defines our experiences.

What is a typical day like for you?

I guess it depends what time of the year it is. During the academic year I spend a lot of time planning my classes and tending to the administrative side of my art career: writing grants, applying to residencies, and planning exhibitions. In the summer time, I usually attend an artist residency or two. This is where I get the majority of my creative work done. These days are much more interesting (to me, at least). I might work in the studio all morning, break for lunch, work some more, then go outside and hike or bike. I really like residencies because of the way studio time is balanced with social interactions—and the other residents are usually very remarkable people. So the conclusion of an ideal day might include a group dinner then some late night studio time working and listening to music.

What are some of the biggest challenges that you have overcome as an artist so far in your career?

Time management. That scenario I described above has worked out OK for the last few years, but is not really sustainable. I've never been good at juggling my creative workflow with teaching. That's not to say that teaching hasn't been integral to my development as an artist. Teaching and making has, in many ways, been a symbiotic practice—my work informs my teaching, and my teaching sustains my work. I just have a really hard time tapping into the creative part of me—the part where the overthinking stops and the making starts—when I am in the academic environment.

What is the art scene like in Detroit?

The art scene in Detroit is vibrant and growing. There are tons of working artists, great non-profit spaces both in the city and in Metro Detroit, and recently there are more commercial galleries opening spaces in the city proper. Sometimes (most times) there are so many openings on a weekend that I can't even get to them all.

What is your favorite studio-workathon food?

Coffee.

What do you listen to while you work? Is this an important part of your practice?

Yes, I love to listen to music. I have pretty eclectic tastes in music, but I've always fancied troubadours. My all time favorites are Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen, Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, and Silvio Rodriguez. My recent obsessions are Jason Isbell, Phosphorescent, and Bonnie "Prince" Billy.

Has there ever been a book/essay/poem/film/etc that totally changed or influenced you? What are you reading right now?

I hate to sound like a photo-geek, but Susan Sontag was pretty influential. On Photography concisely and eloquently stated the problems of photography that continue to interest me. I'm reading about mountains right now: Heights of Reflection edited by Sean Iretone and Caroline Schaumann, and Landscape and Power by W.J.T. Mitchell. Before those, I read The Martian.

What are some of the artists that you look at feel that your work is in dialogue with?

The contemporary artists that I'm looking at right now are Letha Wilson and Abigail Reynolds. I am drawn to their attention to the materiality of the photograph. I am also really interested in John Pfahl and Georges Russe for their play with perspectival illusion.

Do you have any advice for recent grads that are looking for teaching jobs, transitioning out of graduate school, or looking to begin their career as studio artists?

Get a studio. Start a critique group. And if you want to teach, start building the résumé with adjunct work. I think the thing that lacks most when you finish grad school is that built-in community. Finding people that you can talk to about your work is really important. Getting honest feedback after grad school is golden and should be treasured.

Do you have any exciting news or shows coming up?

Yes, thank you for asking! I will have some work in the exhibition "Processed Landscapes" at HEREart in New York City in January and some pieces from Impossible Geometries in "The West" at Drive-by Projects in Watertown, MA. I also have solo exhibitions at 621 Gallery in Talahassee, FL and the Appalachian Center for Craft in Tennessee in the spring. I am particularly excited to have work in "Photography and America's National Parks" at the George Eastman Museum this summer.

Congrats! Thanks so much for sharing your work and talking with us!

To find out more about Millee and her work, check out her website.